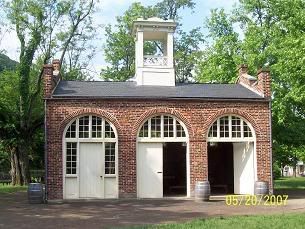

On May 20, we set out for Harper's Ferry, VA, now West Virginia. Abolitionist John Brown led an armed group in the capture of the armory in 1859. Brown had hoped he would be able to arm the slaves and lead them against U.S. forces in a rebellion to overthrow slavery. After his capture in the armory by a group of marines (led by U.S. Army Colonel Robert E. Lee), Brown was hanged, predicting in his last words that civil war was looming on the horizon, a prediction that came true less than two years later. The most important building remaining from John Brown's raid is the firehouse, now called John Brown's Fort where he resisted the Marines.

On May 20, we set out for Harper's Ferry, VA, now West Virginia. Abolitionist John Brown led an armed group in the capture of the armory in 1859. Brown had hoped he would be able to arm the slaves and lead them against U.S. forces in a rebellion to overthrow slavery. After his capture in the armory by a group of marines (led by U.S. Army Colonel Robert E. Lee), Brown was hanged, predicting in his last words that civil war was looming on the horizon, a prediction that came true less than two years later. The most important building remaining from John Brown's raid is the firehouse, now called John Brown's Fort where he resisted the Marines.The American Civil War (1861–1865) found Harpers Ferry right on the boundary between the Union and Confederate forces. The strategic position along this border and the valuable manufacturing base was a coveted strategic goal for both sides, but particularly the South due to its lack of manufacturing centers. Consequently, the town exchanged hands no less than eight times during the course of the war. Union forces abandoned the town immediately after the state of Virginia seceded from the Union, burning the armory and seizing 15,000 rifles. Colonel Thomas J. Jackson, who would later become known as "Stonewall", secured the region for the Confederates a week later and shipped most of the manufacturing implements south. Jackson spent the next two months preparing his troops and building fortifications, but was ordered to withdraw south and east to assist P.G.T. Beauregard at the First Battle of Bull Run. Union troops returned in force, occupying the town and began to rebuild parts of the armory. Stonewall Jackson, now a major general, returned in September 1862 under orders from Robert E. Lee to retake the arsenal and then to join Lee's army north in Maryland. Jackson's assault on the Federal forces at Harpers Ferry led to the capitulation of 12,500 Union troops, which was the largest number of Union prisoners taken at one time during the war. The town exchanged hands several more times over the next two years.

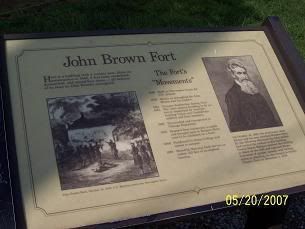

Brown's nicknames were Osawatomie Brown, Old Man Brown, Captain Brown and Old Brown of Kansas. His aliases were "Nelson Hawkins," "Shubel Morgan," and "Isaac Smith." Later the song John Brown's Body became a Union marching song during the Civil War.

I was really looking forward today, especially visiting the hallowed ground at Antietam. We began the day journeying to Harper’s Ferry, site of John Brown’s infamous raid. Harper’s Ferry was interesting to see a town where devastation and desolation actually worked in favor of historical preservation. The reason I say this is that flooding and post Civil War issues led to the town being abandoned, leading to negative economics for the town but positive developments for historical preservation. Given what is there, it is hard at times to think of Harper’s Ferry as being a perfect illustration of American industrialization, but that is where our tour and guide come in. Looking at the gun works, and truly thinking about the key location of the town—with its key access to water power, ore, and transportation, it is easy to see where it could be advantageous to put a town there. It reminds me of the stories of my own hometown, hard to think that during the late 19th century there were 20 saloons in the area, where now there is nary a store or business other than a homegrown junkshop.

It was interesting to note the founding of the Ferry, by a squatter, who hornswaggled Mr. Harper into having to buy the land twice, once from Stevens the squatter, and once again from Lord Fairfax, the deeded owner of the land. Also, the relationships to Presidents was something I did not know, that it was Washington who sanctioned the armory and arsenal; and Thomas Jefferson who looked out on the great view of the town from Jefferson’s Rock.

Our tour ranger/ guide was William Harris, and it was great at how animated he was and how he kept the audience into the presentation. While some in our group were let down that this was not a “reenactment”, I did not mind, as it was great to hear a good storyteller who worked so hard at his craft to learn the facts.

Basically, from Harper’s Ferry I noted the madness of John Brown. The man thought he could hold a town and get slaves to turn on their masters with just a handful of men. Granted, he did cause trouble for three days in 1859, but most of this came from the shock that caught people unawares, thinking Brown was a deranged lunatic who really had no way of taking the town. While they underestimated Brown’s short term capabilities, in the long run they were right. I also learned that the United States Marine Corps lists this as an official battle because the Corps sustained casualties.

View of historic Harper's Ferry

painting of Harper's Ferry as it was, at the time of Brown's Raid. Look at how industrialized it is.

description of John Brown's fort...He had 40 people in here, along with 2 fire engines. The fort was knocked down, then taken to Chicago's 1895 world's fair and rebuilt, knocked down, then a farm, then the former Storer College campus, then to its present location. The park service is thinking of moving it to its original spot.

The fort itself

Marker of original location of the firehouse/fort

remains of lock system around Harper's Ferry.

The group also hiked up to Jefferson's rock, where Thomas Jefferson admired the view. We also walked through some of the historical buildings and shops. My dogs were barking. While Harper’s Ferry was fascinating with the story of John Brown and the dedication of some to have Brown’s Fort restored, I wish we would have spent more time at Antietam. While I appreciate the role of Brown’s Raid in terms of being a rallying point for abolitionists and a cause of paranoia among pro-slavers, I felt Antietam was worth more of our time.

Whenever I have had the opportunity to go to historic battlefields where even a few died, I am humbled and moved. Such was the case with Antietam. While I may discount some of the length of Harper’s Ferry, the guide there was very helpful. At Antietam, it seemed a little less so. The film about Lincoln’s visit to Antietam was much in the same vein as the film shown at Wheeling and the Independence Custom House in terms of its over the top melodrama. However, it did make me think about military leadership and leadership in general. While McClellan may have been respected by his men for drilling them and keeping them out of danger, I have yet to see anywhere we have been the amount of dedication I see to General Lee on the Rebel side, or Sherman on the Union, or in later wars, Patton, Ike, etc. McClellan, much like Brown, seemed to have a messiah complex. For Brown, it led to rash and foolish action in terms of believing he could actually start a new state in the Old Dominion of Virginia by trying to take an arsenal with a handful of men and a few slaves who didn’t know whether to fight or fall back. For McClellan, it came in the form of puffing up his deeds, and being overly cautious so as to avoid bad press or to avoid taking casualties or hurting his record. Different extremes, but similar personality flaws in the need to be noticed. I have a disdain for McClellan, because he was so tardy, in some cases I think it led to more deaths in the war. While later leaders like Grant and Sherman would be charged at times for being brutal and rash, their men loved them; and they won battles. They proved their mettle not with self-promoting letters and propaganda, but by pushing their men to reach down and give a bit more. I think, and history justifies, their place as good leaders while McClellan is largely an historical footnote of the war.

Travelling from the Cornfield to the West Woods and the Sunken Road, it was hard to picture the devastation. While we did not have a tour guide, we did have a cd that did a decent job, and the handbook that I bought with illustrations helped supplement. The brutality that occurred then contrasted with the tranquility of the now. While I loved the opportunity to come to the hallowed ground of Antietam in Sharpsburg, I was disappointed in some of my fellow travelers. They were complaining about being tired and wanting to go home, or making googly eyes at a significant other, or griping about how they did not want to get out of the vehicle. Contrast this with the brave men (and, as the CD said, women) who had to march for miles, only to have to jump into the heat of battle at the quick step both here and at Gettysburg. Kind of makes one think a bit about perspective. I am not going to be unfair…I didn’t like climbing up to Jefferson’s Rock, going to some of the shops, or working my sore knee. However, I knew what I had signed on for. When I reached my limit, I slowed down. I did not go to look at the church ruins in Harper’s Ferry. It just seemed a tad disrespectful to the fallen dead to so think about oneself and griping about how tired we were, and pushing for a speedier conclusion to the day, when some of us would have liked to walk the battlefield more. I consider it a sacred honor to tread in the path of such people—whether they be Gen. John Hood, George McClellan, or just the mess boy who fell in battle. Regardless, all fought for what they believed in, and they deserved more respect.

However, it was an amazing experience. Looking over the monuments, trying to imagine the carage at Bloody Lane, the Cornfield, feeling the sacred nature of the cemetery, all were things I can never forget. Getting some of the same perspective as our forbears is an amazing thing.

The other thing of note was all the future big namers in this battle. It was almost like a “before they were stars” situation. You had Clara Barton, who would found the American Red Cross, Captain Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr—who would go on to be a Supreme Court Justice (and who also got to call Lincoln a fool for being exposed to Rebel snipers, and got away with it), future Presidents Rutherford B. Hayes and William McKinley, both from my home state of Ohio.

I also read with interest the story of Thomas Meagher, who led the famous Irish Brigade and actually introduced the tricolor that became Ireland’s flag. These types of bits of history are fascinating. So far, with the exception of the car ride, this trip has been beyond my expectations.

The Battle of Antietam (also known as the Battle of Sharpsburg, particularly in the South), fought on September 17, 1862, near Sharpsburg, Maryland, and Antietam Creek, as part of the Maryland Campaign, was the first major battle in the American Civil War to take place on Northern soil. It was the bloodiest single-day battle in American history, with almost 23,000 casualties.[1]

After pursuing Confederate General Robert E. Lee into Maryland, Union Army Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan launched attacks against Lee's army, in defensive positions behind Antietam Creek. At dawn on September 17, Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker's corps mounted a powerful assault on Lee's left flank. Attacks and counterattacks swept across Miller's cornfield and fighting swirled around the Dunker Church. Union assaults against the Sunken Road eventually pierced the Confederate center, but the Federal advantage was not followed up. Late in the day, Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside's corps finally got into action, crossing the stone bridge over Antietam Creek and rolling up the Confederate right. At a crucial moment, Maj. Gen. A.P. Hill's division arrived from Harpers Ferry and counterattacked, driving back Burnside and saving the day. Although outnumbered two-to-one, Lee committed his entire force, while McClellan sent in less than three-quarters of his army, enabling Lee to fight the Federals to a standstill. During the night, both armies consolidated their lines. In spite of crippling casualties, Lee continued to skirmish with McClellan throughout September 18, while removing his wounded south of the river.[2]

Despite having superiority of numbers, McClellan's attacks failed to achieve concentration of mass, allowing Lee to counter by shifting forces to meet each challenge. Despite ample reserve forces that could have been deployed to exploit localized successes, McClellan failed to destroy Lee's army. Nevertheless, Lee's invasion of Maryland was ended, and he was able to withdraw his army back to Virginia without interference from the cautious McClellan. Although the battle was tactically inconclusive, it had unique significance as enough of a victory to give President Abraham Lincoln the confidence to announce his Emancipation Proclamation.

Dunker Church at the battlefield as it looks today

[NOTE: This photo was removed due to its size causing formatting problems with the sidebar. I'll try to get Mark to resize it. - MATT]

Dunker Church right shortly after the battle...

[NOTE: This photo was removed due to its size causing formatting problems with the sidebar. I'll try to get Mark to resize it. - MATT]

Monument to Clara Barton, founder of the American Red Cross, note the red cross at the base...she was called the angel of the battlefield

upside down cannon marking where Ma. Gen. Joseeph Mansfield CSA's 2 day career as a field commander came to an end in the east woods.

McClellan's plans were ill-coordinated and were executed poorly. He issued to each of his subordinate commanders only the orders for his own corps, not general orders describing the entire battle plan. The terrain of the battlefield made it difficult for those commanders to monitor events outside of their sectors, and McClellan's headquarters were more than a mile in the rear (at the Philip Pry house, east of the creek), making it difficult for him to control the separate corps. Therefore, the battle progressed the next day as essentially three separate, mostly uncoordinated battles: morning in the northern end of the battlefield, mid-day in the center, and afternoon in the south. This lack of coordination and concentration of McClellan's forces almost completely nullified the two-to-one advantage the Union enjoyed and allowed Lee to shift his defensive forces to meet each offensive.

Morning

Assaults by the I Corps, 5:30 to 7:30 a.m.The battle opened at dawn (about 5:30 a.m.) on September 17 with an attack down the Hagerstown Turnpike by the Union I Corps under Joseph Hooker. Hooker's objective was the plateau on which the Dunker Church sat, a modest whitewashed building belonging to a local sect of German Baptists. Hooker had approximately 8,600 men, little more than the 7,700 defenders under Stonewall Jackson, and this slight disparity was more than offset by the Confederates' strong defensive positions.[11] Abner Doubleday's division moved on Hooker's right, James Ricketts's moved on the left into the East Woods, and George Meade's Pennsylvania Reserves division deployed in the center and slightly to the rear. Jackson's defense consisted of the divisions under Alexander Lawton and John R. Jones in line from the West Woods, across the Turnpike, and along the southern end of the Miller Cornfield. Four brigades were held in reserve inside the West Woods.[12]

As the first Union men emerged from the North Woods and into the Cornfield, an artillery duel erupted. Confederate fire was from the horse artillery batteries under Jeb Stuart to the west and four batteries under Col. Stephen D. Lee on the high ground across the pike from the Dunker Church to the south. Union return fire was from nine batteries on the ridge behind the North Woods and four batteries of 20-pounder Parrott rifles, 2 miles (3 km) east of Antietam Creek. The conflagration caused heavy casualties on both sides and was described by Col. Lee as "artillery Hell."[13]

Seeing the glint of Confederate bayonets concealed in the Cornfield, Hooker halted his infantry and brought up four batteries of artillery, which fired shell and canister over the heads of the Federal infantry, covering the field. The artillery and rifle fire from both sides acted like a scythe, cutting down cornstalks and men alike.

Meade's 1st Brigade of Pennsylvanians, under Brig. Gen. Truman Seymour, began advancing through the East Woods and exchanged fire with Colonel James Walker's brigade of Alabama, Georgia, and North Carolina troops. As Walker's men forced Seymour's back, aided by Lee's artillery fire, Ricketts's division entered the Cornfield, also to be torn up by artillery. Brig. Gen. Abram Duryée's brigade marched directly into volleys from Colonel Marcellus Douglass's Georgia brigade. Enduring heavy fire from a range of 250 yards and gaining no advantage because of a lack of reinforcements, Duryée ordered a withdrawal.[12]

The reinforcements that Duryée had expected—brigades under Brig. Gen. George L. Hartsuff and Col. William A. Christian—had difficulties reaching the scene. Hartsuff was wounded by a shell, and Christian dismounted and fled to the rear in terror. When the men were rallied and advanced into the Cornfield, they met the same artillery and infantry fire as their predecessors. As the superior Union numbers began to tell, the Louisiana "Tiger" Brigade under Harry Hays entered the fray and forced the Union men back to the East Woods. The casualties received by the 12th Massachusetts Infantry, 67%, were the highest of any unit that day.[14] The Tigers were beaten back eventually when the Federals brought up a battery of 3-inch ordnance rifles and rolled them directly into the Cornfield, point-blank fire that slaughtered the Tigers, who lost 323 of their 500 men.[15]

While the Cornfield remained mired in a bloody stalemate, Federal advances a few hundred yards to the west were more successful. Brig. Gen. John Gibbon's 4th Brigade of Doubleday's division (recently named the Iron Brigade) advanced down the turnpike, pushing aside Jackson's men. They were halted by a charge of 1,150 men from Starke's brigade, leveling heavy fire from 30 yards away. After Starke was mortally wounded and exposed to fierce return fire from the Iron Brigade, the Confederate brigade withdrew.[16] The Union advance on the Dunker Church resumed and cut a large gap in Jackson's defensive line, which teetered near collapse. Although the cost was steep, Hooker's corps was making steady progress.

Confederate reinforcements arrived just after 7 a.m. The divisions under McLaws and Richard H. Anderson arrived following a night march from Harpers Ferry. Around 7:15, General Lee moved George T. Anderson's Georgia brigade from the right flank of the army to aid Jackson.

At 7 a.m., Hood's division of 2,300 men advanced through the West Woods and pushed the Union troops back through the Cornfield again. The Texans attacked with particular ferocity because as they were called from their reserve position they were forced to interrupt the first hot breakfast they had had in days. They were aided by three brigades of D.H. Hill's division arriving from the Mumma Farm, southeast of the Cornfield, and by Jubal Early's brigade, pushing through the West Woods from the Nicodemus Farm, where they had been supporting Jeb Stuart's horse artillery. Hood's men bore the brunt of the fighting, however, and paid a heavy price—60% casualties—but they were able to prevent the defensive line from crumbling and held off the I Corps. When asked by a fellow officer where his division was, Hood replied, "Dead on the field."[17]

Hooker's men had also paid heavily but without achieving their objectives. After two hours and 2,500 casualties, they were back where they started. The Cornfield, an area about 250 yards deep and 400 yards wide, was a scene of indescribable destruction. It was estimated that the Cornfield changed hands no fewer than 15 times in the course of the morning.[18] Hooker called for support from the 7,200 men of Mansfield's XII Corps.

... every stalk of corn in the northern and greater part of the field was cut as closely as could have been done with a knife, and the [Confederates] slain lay in rows precisely as they had stood in their ranks a few moments before.

—Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker

Assaults by the XII Corps, 7:30 to 9:00 a.m.Half of Mansfield's men were raw recruits, and Mansfield was also inexperienced, having taken command only two days before. Although he was a veteran of 40 years' service, he had never led large numbers of soldiers in combat. Concerned that his men would bolt under fire, he marched them in a formation that was known as "column of companies, closed in mass," a bunched-up formation in which a regiment was arrayed ten ranks deep instead of the normal two. As his men entered the East Woods, they presented an excellent artillery target, "almost as good a target as a barn." Mansfield himself was felled by a sniper's bullet and died later in the day. Alpheus Williams assumed temporary command of the XII Corps.[19]

The new recruits of Mansfield's 1st Division made no progress against Hood's line, which was reinforced by D.H. Hill's divisions under Colquitt and McRae. The 2nd Division of the XII Corps, under George Sears Greene, however, broke through McRae's men, who fled under the mistaken belief that they were about to be trapped by a flanking attack. This breach of the line forced Hood and his men, outnumbered, to regroup in the West Woods, where they had started the day.[14] Greene was able to reach the Dunker Church, Hooker's original objective, and drove off Stephen Lee's batteries. Federal forces held most of the ground to the east of the turnpike.

Hooker attempted to gather the scattered remnants of his I Corps to continue the assault, but a Confederate sharpshooter spotted the general's conspicuous white horse and shot Hooker through the foot. Command of his I Corps fell to General Meade, since Hooker's senior subordinate, James B. Ricketts, had also been wounded. But with Hooker removed from the field, there was no general left with the authority to rally the men of the I and XII Corps. Greene's men came under heavy fire from the West Woods and withdrew from the Dunker Church.

In an effort to turn the Confederate left flank and relieve the pressure on Mansfield's men, Sumner's II Corps was ordered at 7:20 a.m. to send two divisions into battle. Sedgwick's division of 5,400 men was the first to ford the Antietam, and they entered the East Woods with the intention of turning left and forcing the Confederates south into Ambrose Burnside's IX Corps. But the plan went awry. They became separated from William H. French's division, and at 9 a.m. Sumner recklessly launched the division attack en masse without adequate reconnaissance. They were assaulted from three sides, and in less than half an hour their momentum was stopped with over 2,200 casualties.[14]

The final actions in the morning phase of the battle were around 10 a.m., when two regiments of the XII Corps advanced, only to be confronted by the division of John G. Walker, newly arrived from the Confederate right. They fought in the area between the Cornfield in the West Woods, but soon Walker's men were forced back by two brigades of Greene's division, and the Federal troops seized some ground in the West Woods.

The morning phase ended with casualties on both sides of almost 13,000, including two Union corps commanders.[20]

Shot of the Cornfield today

another shot of the Cornfield

Mid-day

Assaults by the XII and II Corps, 9 a.m. to 1 p.m.By mid-day, the action shifted to the center of the Confederate line. Sumner had accompanied the morning attack of Sedgwick's division, but another of his divisions, under French, lost contact with Sumner and Sedgwick and inexplicably headed south. Eager for an opportunity to see combat, French found skirmishers in his path and ordered his men forward. By this time, Sumner's aide (and son) located French, described the terrible fighting in the West Woods and relayed an order for him to divert Confederate attention by attacking their center.[21]

French confronted D.H. Hill's division. Hill commanded about 2,500 men, less than half the number under French, and three of his five brigades had been torn up during the morning combat. This sector of Longstreet's line was theoretically the weakest. But Hill's men were in a strong defensive position, atop a gradual ridge, in a sunken road worn down by years of wagon traffic, which formed a natural trench.[22]

French launched a series of brigade-sized assaults against Hill's improvised breastworks at around 9:30 a.m. The first brigade to attack, mostly inexperienced troops commanded by Brig. Gen. Max Weber, was quickly cut down by heavy rifle fire (neither side deployed artillery at this point.) The second attack, more raw recruits under Col. Dwight Morris, was also subjected to heavy fire but managed to beat back a counterattack by the Alabama Brigade of Robert Rodes. The third, under Brig. Gen. Nathan Kimball, included three veteran regiments, but they also fell to fire from the sunken road. French's division suffered 1,750 casualties (of his 5,700 men) in under an hour.[23]

Reinforcements were arriving on both sides, and by 10:30 a.m. Robert E. Lee sent his final reserve division—some 3,400 men under Maj. Gen. Richard H. Anderson—to bolster Hill's line and extend it to the right, preparing an attack that would envelop French's left flank. But at the same time, the 4,000 men of Maj. Gen. Israel B. Richardson's division arrived on French's left. This was the last of Sumner's three divisions, which had been held up in the rear by McClellan as he organized his reserve forces.[24] Richardson's fresh troops struck the first blow.

Leading off the fourth attack of the day against the sunken road was the Irish Brigade of Brig. Gen. Thomas F. Meagher. As they advanced with emerald green flags snapping in the breeze, a regimental chaplain, Father William Corby, rode back and forth across the front of the formation shouting words of conditional absolution prescribed by the Roman Catholic Church for those who were about to die. (Corby performed a similar service at Gettysburg in 1863.) The mostly Irish immigrants lost 540 men to heavy volleys before they were ordered to withdraw.[25]

Gen. Richardson personally dispatched the brigade of Brig. Gen. John C. Caldwell into battle around noon (after being told that Caldwell was in the rear, behind a haystack), and finally the tide turned. Anderson's Confederate division had been little help to the defenders after Gen. Anderson was wounded early in the fighting. Other key leaders were lost as well, including George B. Anderson (no relation) and Colonel John B. Gordon of the 6th Alabama. (Gordon received four serious wounds in the fight. He lay unconscious, face down in his cap, and later told colleagues that he should have smothered in his own blood, except for the act of an unidentified Yankee, who had earlier shot a hole in his cap, which allowed the blood to drain.)[26] Rodes was wounded in the thigh but was still on the field. These losses contributed directly to the confusion of the following events.

We were shooting them like sheep in a pen. If a bullet missed the mark at first it was liable to strike the further bank, angle back, and take them secondarily.

—Sergeant of the 61st New York[27]

As Caldwell's brigade advanced around the right flank of the Confederates, Col. Francis C. Barlow and 350 men of the 61st and 64th New York saw a weak point in the line and seized a knoll commanding the sunken road. This allowed them to get enfilade fire into the Confederate line, turning it into a deadly trap. In attempting to wheel around to meet this threat, a command from Gen. Rodes was misunderstood by Lt. Col. James N. Lightfoot, who had succeeded the unconscious John Gordon. Lightfoot ordered his men to about-face and march away, an order that all five regiments of the brigade thought applied to them as well. Confederate troops streamed toward Sharpsburg, their line lost.

Richardson's men were in hot pursuit when massed artillery hastily assembled by Gen. Longstreet drove them back. A counterattack with 200 men led by D.H. Hill got around the Federal left flank near the sunken road, and although they were driven back by a fierce charge of the 5th New Hampshire, this stemmed the collapse of the center. Reluctantly, Richardson ordered his division to fall back to north of the ridge facing the sunken road. His division lost about 1,000 men. Col. Barlow was severely wounded, and Richardson mortally wounded.[28] Winfield S. Hancock assumed division command. Although Hancock would have an excellent future reputation as a division and corps commander, the unexpected change of command sapped the momentum of the Federal advance.[29]

The Bloody Lane in 2005.The carnage from 9:30 a.m. to 1:00 p.m. on the sunken road gave it the name Bloody Lane, leaving about 5,600 casualties (Union 3,000, Confederate 2,600) along the 800-yard road. And yet a great opportunity presented itself. If this broken sector of the Confederate line were exploited, Lee's army would have been divided in half and possibly defeated. There were ample forces available to do so. There was a reserve of 3,500 cavalry and the 10,300 infantrymen of Gen. Porter's V Corps, waiting near the middle bridge, a mile away. The VI Corps had just arrived with 12,000 men. Maj. Gen. William B. Franklin of the VI Corps was ready to exploit this breakthrough, but Sumner, the senior corps commander, ordered him not to advance. Franklin appealed to McClellan, who left his headquarters in the rear to hear both argument

Later in the day, the commander of the other reserve unit near the center, the V Corps, Maj. Gen. Fitz John Porter, heard recommendations from Maj. Gen. George Sykes, commanding his 2nd Division, that another attack be made in the center, an idea that intrigued McClellan. However, Porter is said to have told McClellan, "Remember, General, I command the last reserve of the last Army of the Republic." McClellan demurred and another opportunity was lost.[31]s but backed Sumner's decision, ordering Gens. Franklin and Hancock to hold their positions.[30]

The Sunken Road

Another pic of The Sunken Road

The 132nd Pennsylvania Monument--Took part in French's attack on the Sunken Road. Nine month enlistment regiment, mustered in Sept. 1862 and retired May 1863. Took part in some of the heaviest fighting, at Antietam, Fredericksburg, and Chancellorsville. While marching past the Roulette farm house at Antietam, a Confederate artillery shot slammed into a row of the family's beehives. The angry swarm of bees immediately attacked the green recruits, as they pushed forward amidst a hail of confederate bullets.

Looking the other way, eastward, on the Sunken Road, or Bloody Lane. Note the observation tower built by the War Department in 1896. Still used to train military personnel in this battlefield classroom.

Monument to the Irish Brigade--Thomas Meagher ws an Irish revolutionist who made his way to New York, where he recruited the Irish Brigade, a famous unit who fought at Bloody Lane in Antietam, the Stone Wall at Fredericksburg, as well as Gettysburg. Meagher was responsible for introducing the tricolor which would become Ireland's national flag.

Afternoon

Assaults by the IX Corps, 10 a.m. to 4:30 p.m.The action moved to the southern end of the battlefield. McClellan's plan called for Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside and the IX Corps to conduct a diversionary attack in support of Hooker's I Corps, hoping to draw Confederate attention away from the intended main attack in the north. However, Burnside was instructed to wait for explicit orders before launching his attack, and those orders did not reach him until 10 a.m.[32] Burnside was strangely passive during preparations for the battle. He was disgruntled that McClellan had abandoned the previous arrangement of "wing" commanders reporting to him. Previously, Burnside had commanded a wing that included both the I and IX Corps and now he was responsible only for the IX Corps. Implicitly refusing to give up his higher authority, Burnside treated first Maj. Gen. Jesse L. Reno (killed at South Mountain) and then Brig. Gen. Jacob D. Cox of the Kanawha Division as the corps commander, funneling orders to the corps through him.

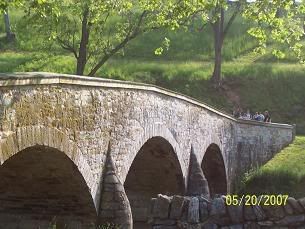

Burnside had four divisions (12,500 troops) and 50 guns east of Antietam Creek. Facing him was a force that had been greatly depleted by Lee's movement of units to bolster the Confederate left flank. At dawn, the divisions of Brig. Gens. David R. Jones and John G. Walker stood in defense, but by 10 a.m. all of Walker's men and Col. George T. Anderson's Georgia brigade had been removed. Gen. Jones had only about 3,000 men and 12 guns available to meet Burnside. Four thin brigades guarded the ridges near Sharpsburg, primarily a low plateau known as Cemetery Hill. The remaining 400 men—the 2nd and 20th Georgia regiments, under the command of Brig. Gen. Robert Toombs, with two artillery batteries—defended Rohrbach's Bridge, a three-span, 125-foot (38 m) stone structure that was the southernmost crossing of the Antietam.[33] It would become known to history as Burnside's Bridge because of the notoriety of the coming battle. The bridge was a difficult objective. The road leading to it ran parallel to the creek and was exposed to enemy fire. The bridge was dominated by a 100-foot (30 m) high wooded bluff on the west bank, strewn with boulders from an old quarry, making infantry and sharpshooter fire from good covered positions a dangerous impediment to crossing.

Burnside's Bridge, looking from the Union side to the Confederate side

Another pic of Burnside's bridge

Burnside's Bridge.But Burnside had not performed ample reconnaissance. Antietam Creek in this sector was seldom more than 50 feet (15 m) wide, and several stretches were only waist deep and out of Confederate range. He concentrated his plan instead on storming the bridge and crossing a ford McClellan's engineers had identified a half mile (1 km) downstream, but when the Burnside's men reached it, they found the banks too high to negotiate. While Col. George Crook's Ohio brigade prepared to attack the bridge with the support of Brig. Gen. Samuel Sturgis's division, the rest of the Kanawha Division and Brig. Gen. Isaac Rodman's division struggled through thick brush trying to locate Snavely's Ford, 2 miles (3 km) downstream, intending to flank the Confederates.[33]

Crook's assault on the bridge was led by skirmishers from the 11th Connecticut who were ordered to clear the bridge for the Ohioans to cross and assault the bluff. After receiving punishing fire for 15 minutes, the Connecticut men withdrew with 139 casualties, one third of their strength, including their commander, Col. Henry W. Kingsbury, who was fatally wounded.[34] Crook's main assault went awry when his unfamiliarity with the terrain caused his men to reach the creek a quarter mile (400 m) upstream from the bridge, where they exchanged volleys with Confederate skirmishers for the next few hours.[35]

While Rodman's division was out of touch, slogging toward Snavely's Ford, Burnside and Cox directed a second assault at the bridge by one of Sturgis's brigades, led by the 2nd Maryland and 6th New Hampshire. They also fell prey to the Confederate sharpshooters and artillery, and their attack fell apart.[36] By this time it was noon, and McClellan was losing patience. He sent a succession of couriers to motivate Burnside to move forward. He ordered one aide, "Tell him if it costs 10,000 men he must go now." He increased the pressure by sending his inspector general, Col. Delos B. Sackett, to confront Burnside, who reacted indignantly: "McClellan appears to think I am not trying my best to carry this bridge; you are the third or fourth one who has been to me this morning with similar orders."[37]

The third attempt to take the bridge was at 12:30 p.m. by Sturgis's other brigade, commanded by Brig. Gen. Edward Ferrero. It was led by the 51st New York and the 51st Pennsylvania, who, with adequate artillery support and a promise that a recently canceled whiskey ration would be restored if they were successful, charged downhill and took up positions on the east bank. Maneuvering a captured light howitzer into position, they fired double canister down the bridge and got within 25 yards of the enemy. By 1 p.m., Confederate ammunition was running low, and word reached Toombs that Rodman's men were crossing Snavely's Ford on their flank. He ordered a withdrawal. His Georgians had cost the Federals more than 500 casualties, giving up fewer than 160 themselves. And they had stalled Burnside's assault on the southern flank for more than three hours.[38]

Burnside's assault stalled again on its own. His officers had neglected to transport ammunition across the bridge, which was itself becoming a bottleneck for soldiers, artillery, and wagons. This represented another two-hour delay. Gen. Lee used this time to bolster his right flank. He ordered up every available artillery unit, although he made no attempt to strengthen Gen. Jones's badly outnumbered force with infantry units from the left. Instead, he counted on the arrival of A.P. Hill's Light Division, currently embarked on an exhausting 17 mile (27 km) march from Harpers Ferry. By 2 p.m., Hill's men had reached Boteler's Ford, and Hill was able to confer with the relieved Lee at 2:30, who ordered him to bring up his men to the right of Jones.[39]

The Federals were completely unaware that 3,000 new men would be facing them. Burnside's plan was to move around the weakened Confederate right flank, converge on Sharpsburg, and cut the Lee's army off from Boteler's Ford, their only escape route across the Potomac. At 3 p.m., Burnside left Sturgis's division in reserve on the west bank and moved west with over 8,000 troops (most of them fresh) and 22 guns for close support.[40]

An initial assault led by the 79th New York "Cameron Highlanders" succeeded against Jones's outnumbered division, which was pushed back past Cemetery Hill and to within 200 yards of Sharpsburg. Farther to the left, Rodman's division advanced toward Harpers Ferry Road. Its lead brigade, under Col. Harrison Fairchild, containing several colorful Zouaves of the 9th New York, came under heavy shellfire from a dozen enemy guns mounted on a ridge to their front, but they kept pushing forward. There was panic in the streets of Sharpsburg, clogged with retreating Confederates. Of the five brigades in Jones's division, only Toombs's brigade was still intact, but he had only 700 men.[41]

A. P. Hill's division arrived at 3:30 p.m. Hill divided his column, with two brigades moving southeast to guard his flank and the other three, about 2,000 men, moving to the right of Toombs's brigade and preparing for a counterattack. At 3:40 p.m., Brig. Gen. Maxcy Gregg's brigade of South Carolinians attacked the 16th Connecticut on Rodman's left flank in the cornfield of farmer John Otto. The Connecticut men had been in service for only three weeks, and their line disintegrated with 185 casualties. The 4th Rhode Island came up on the right, but the poor visibility amid the high stalks of corn, and they were disoriented because many of the Confederates were wearing Union uniforms captured at Harpers Ferry. They also broke and ran, leaving the 8th Connecticut far out in advance and isolated. They were enveloped and driven down the hills toward Antietam Creek. A counterattack by regiments from the Kanawha Division fell short.[42]

The IX Corps had suffered casualties of about 20% but still possessed twice the number of Confederates confronting them. Unnerved by the collapse of his flank, Burnside ordered his men all the way back to the west bank of the Antietam, where he urgently requested more men and guns. McClellan was able to provide just one battery. He said, "I can do nothing more. I have no infantry." In fact, however, McClellan had two fresh corps in reserve, Porter's V and Franklin's VI, but he was too cautious, concerned about an imminent massive counterstrike by Lee. Burnside's men spent the rest of the day guarding the bridge they had suffered so much to capture.[43]

[edit] Aftermath

The battle was over by 5:30 p.m. Losses for the day were heavy on both sides. The Union had 12,401 casualties with 2,108 dead. Confederate casualties were 10,318 with 1,546 dead. This represented 25% of the Federal force and 31% of the Confederate.[44] More Americans died on September 17, 1862, than on any other day in the nation's military history, including World War II's D-Day and the terrorist assaults of September 11, 2001.[45] On the morning of September 18, Lee's army prepared to defend against a Federal assault that never came. After an improvised truce for both sides to recover and exchange their wounded, Lee's forces began withdrawing across the Potomac that evening to return to Virginia.

President Lincoln was disappointed in McClellan's performance. He believed that McClellan's cautious and poorly coordinated actions in the field had forced the battle to a draw rather than a crippling Confederate defeat.

Interestingly, William McKinley served under Rutherford B. Hayes, both of Ohio, both future Presidents. McKinley has a monument close by Burnside's Bridge, in honor of his bravery at Antietam in terms of resupplying the troops.

bottom and top of McKinley Monument

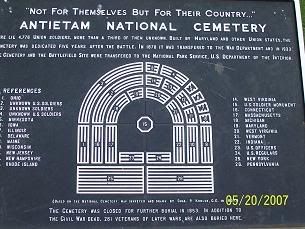

entrance to National Cemetery at Antietam

The Fallen

Outdoor plaque diagram of the cemetery

Old Simon, who stands guard in the middle of the hallowed ground